Sync Fee & Sync Royalties Explained – Where the Money Comes From

May 24, 2023

In sync licensing, songwriters and artists get paid an upfront sync fee for the use of their song in a film, TV, or advertising project. There are two types of sync license fees:

- One sync fee for the use of the song or composition

- And a separate sync fee for the use of the master recording

If you are an independent songwriter or artist (not signed to a label or publisher) and you own both the song and the master, then you would be paid both upfront sync fees.

However, the potential to earn additional income from your sync placement is huge, as we’ll explain in this article.

Music Publishing Royalties

Did you know that aside from music sync fees, in the United States alone, sync royalties (royalties from sync licensing) account for nearly 30% of all music publishing royalties?

Sync licensing is now the second-highest royalty stream for independent artists!

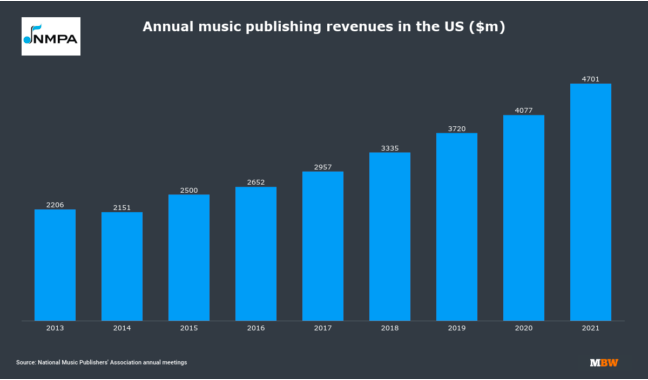

According to Music Business Worldwide, in 2021 music publishing royalties topped 4.7 billion in the United States.

This bar chart by the National Music Publishers Association shows consistent revenue growth since 2015!

What Are Sync Royalties?

There are no actual sync royalties, but you can earn future performance royalties from sync placements.

Whoever you licenced the song to would only have to pay the sync fee once for the sync licensing. That’s it. They have no further obligation to you, and they do not collect any future royalties on your behalf.

However, once you have a sync placement, your song does have great potential for a lot more additional income.

If your song was placed in a TV series that went into syndication, you could potentially be earning performance royalties from that sync placement for years.

Other Sources of Income

If you get a sync placement in a film or TV show, your song may be heard by millions of people.

Many may want to stream or buy the song and even Shazam to find out who the artist is. This is a great way to increase your fan base.

If your song isn’t released this could mean a lot of lost potential income. Your song needs to be on a streaming service like Spotify or Apple, or on your website (if you have one) where potential fans can find it, stream it, or download it.

Make Your Music Available

If you want to capitalize on the potential additional income your song could earn besides the sync fee, I recommend these steps:

- Register your song(s) with your country’s Performing Rights Organization (PRO)

- Release your song(s) so they are available on streaming platforms like Spotify and Apple

- Sign up with a music distribution company like Tunecore, Distrokid, CDBaby

- Create an artist’s website and add your songs for streaming or purchase

- Create a Soundcloud account and add your songs for streaming or purchase

- Have a social presence on Facebook, Instagram, etc., so fans can find and follow you

- Create music videos and post them on YouTube

Understanding Royalties & Your Rights

Let’s talk about the other types of possible royalties you can earn and the sources that do collect and pay these royalties on your behalf.

As a songwriter, you own the copyright for your songs. There are 2 copyrights to every recording:

- The Composition Copyright (the “song” itself)

- The Sound Recording Copyright (or “master”).

Sometimes both copyrights are owned by the same person (if you wrote and recorded the song yourself) and sometimes it’s owned/controlled by your label or publishing company.

If you own the master recording, you also own the publishing. As the copyright owner, you have the following intrinsic rights including the right to reproduce or make a derivative of the song plus, the right to distribute and perform the work.

Your ownership includes:

- COMPOSITION/SONG (PUBLISHING)

- Performance Royalties – If you don’t have a publisher, you are the publisher and own both shares

- Writer’s Share

- Publisher’s Share

- Mechanical Royalties

- Publisher Share

2. MASTER (RECORDING)

- Neighboring Rights

- Master Royalties

Types of Music Royalties You Can Earn Following a Sync Placement

Sync fees are great but that’s just the beginning. After your sync placement, your song can also earn future royalties, but collecting song royalties can take a long time.

Thankfully, there are organizations that will do that on your behalf. These organizations are typically registered with hundreds of societies around the world, so it can take some time to identify and collect royalties on your behalf.

You will need to be a member of some of these organizations if you want to be paid any royalties that your song might earn in your own country and internationally.

Here’s a breakdown of how music royalties are collected and paid on your behalf.

There are three primary sources of music royalties you should be aware of:

- Performance Royalties

- Mechanical Royalties

- Micro-Sync Royalties

Performance Royalties

As mentioned, there really is no such thing as sync royalties. However, after you’ve been paid the sync fee, your song will earn performance royalties whenever it is publicly performed, whether it is a live performance or performed on radio, in film, or on TV.

Your Performing Rights Organization (PRO) will take care of the music rights management. They will collect the performance royalties on your behalf and will pay the performance royalties collected directly to you, the songwriter.

In the United States, the PROs are Broadcast Music Inc. (BMI) and the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP).

In Canada, it’s the Society of Composers, Authors and Music Publishers (SOCAN).

Every country will have its own PRO.

If you perform your own song live, in most cases you can register your setlist with your PRO to get paid for it.

If you have an admin publishing company, you do not need to register your songs with your PRO. Your admin publishing company will register your songs with your PRO on your behalf.

Mechanical Royalties

How do you get mechanical royalties from streaming services?

These royalties go to the Mechanical Rights Organization (MRO) and get paid to either your publishing company or you directly if you don’t have a publishing (or admin publishing) company.

Mechanical royalties are paid whenever your song is physically reproduced or streamed through a streaming service. It encompasses both physical and digital copies.

In the United States, the only MRO is the Mechanical Licensing Collective (MLC).

In Canada, it’s the Canadian Music Reproduction Rights Agency (CMRRA).

If you are your own publisher, the MRO would pay you the Mechanical Royalties that your song earns. To collect, you must be signed up directly with the MRO.

Royalties Paid Through Neighboring Rights Organizations

How do you get recording performance royalties?

You can get performance royalties either through:

- SoundExchange in the USA

- Or from a Neighboring Rights Organization if outside the USA

SoundExchange – In the United States, SoundExchange is responsible for collecting and paying out the recording performance royalties that are collected from digital radio (like Pandora, Sirius/XM and iHeart). These royalties are paid to the Artists, record labels, and non-featured artists (session musicians) on the recording.

Neighboring Rights Organizations – Outside the US, Neighboring Rights Organizations are responsible for collecting recording performance royalties (from radio, TV, live venues, etc.).

Micro-Sync Royalties

Music videos on YouTube earn royalties as well. YouTube will pay you these Micro-Sync Royalties whenever your song is played in videos created by others.

Streaming Royalties

Streaming royalties are relatively new. It is typically a combination of performance and mechanical royalties, and the rates vary between platforms. For instance, as of this writing, Apple Music pays only $0.01 per play whereas Spotify pays between $.003 and $.005 per stream.

Summary

The key takeaway from all this is, “Don’t leave money on the table.”

Earning a sync fee from a sync placement in film or TV is just the beginning.

There have been many relatively obscure indie artists that fans have discovered through sync placements. Be sure to get all your ducks in line so you can take advantage of the exposure that a sync placement can bring to you and your music.

About Sync Songwriter

Sync Songwriter was created to help introduce indie songwriters and artists to the world of music sync licensing.

The sync licensing industry has grown exponentially in the past decade. This has created exceptional opportunities for musicians, songwriters, and artists.

Along with earning additional income through a sync fee and future performance royalties, sync placements have helped to expose indie artists and songwriters to a world of new fans.

Chris SD is a JUNO award-winning music producer. Over the past decade, he has been teaching indie songwriters and artists how to improve their odds and succeed in sync licensing.

Sync Songwriter courses will teach you:

- How the sync licensing world works

- How to improve your songwriting skills

- How to improve the production quality of your songs so they can compete

- How to prepare your songs like a pro for sync licencing

- How to find sync opportunities

- How to research, approach, and build relationships with TV and film music supervisors

- How to submit songs for sync placement

- What you need to know about the business side of sync licensing

At Sync Songwriter, we also introduce you to some of the film and TV’s top music supervisors!

If you’ve ever wanted to be in that top percentage of artists and musicians that music supervisors trust and are willing to hear music from, Sync Songwriter can help you get there.

TV and film music supervisors look for all types of music, from all types of genres.

Contact Sync Songwriter

Let us show you how you can increase your chances of getting your music heard and placed in TV, film, and advertising.

If you still have questions about sync fees or how you can earn royalties from music sync licensing, please contact Sync Songwriter.

Leave a Reply

Hey! Give us a shout about anything really.

contact Sync Songwriter

Our goal is for you to start getting your music into TV & film.

Hi Chris,

Thanks so much for all you do.

I’m going through the process, and I think I have 3 contenders for review. A couple of questions though:

1. I’m the songwriter, and I’ve played all instruments and vocals except for some BUV’s, drums, and bass. I’m sure I own the PA rights, and I share SR rights with my bass/drum player, as mutually agreed.

For the BUV’s singers, do I need some form completed (i.e. “Work for Hire”) in order to put “one stop” in the meta data? Would they have any composition rights? How do you suggest working with outside talent, w/o complicating the licensing process? I also write children’s music, and I’ve considered working with a local talent school to have some of their students cut vocals for some of my tunes. What legal considerations arise from such a venture?

Thanks again for the input. BTW…loved your “R” bike! I’ve got K1200S that I adore, but it’s probably getting traded for a Neve 2484. We’ll see.

Cheers.

Hi Scott,

Thanks for your kind words and for asking these great questions.

1. In order for you to list yourself as “one-stop” in your metadata, you would need to get a one-stop agreement signed/ completed by all other copyright owners of the track (on the composition as well as master side). In your case, you would have to get your bass/drum player to sign off on a one-stop agreement, permitting you to shop the song on their behalf.

2. That being said, it is certainly important to have work for hire agreements written out and signed by all parties involved on the track, as this helps ensure that everyone’s on the same page and helps avoid headaches down the line. If you have hired a work-for-hire musician to play on the track, they would not be entitled to any composition rights. However, it is always a good idea to get work-for-hire agreements signed as proof of this arrangement. This will cover your bases with regards to working with outside hires. From here, you would only need to split your sync fees/ earnings with the co-owners of your track, which in your case is your bass/drum player.

3. Although we cannot give you legal advice, I can suggest that it would be a good idea to consult with the parents/ legal guardians of the children and then obtain work-for-hire agreements just as you would any other performer/musician, but with the parents/guardians signing on behalf of the children.

I hope that helps!